Welcome to markorear.com, a website dedicated to exploring the O'Rear lineage

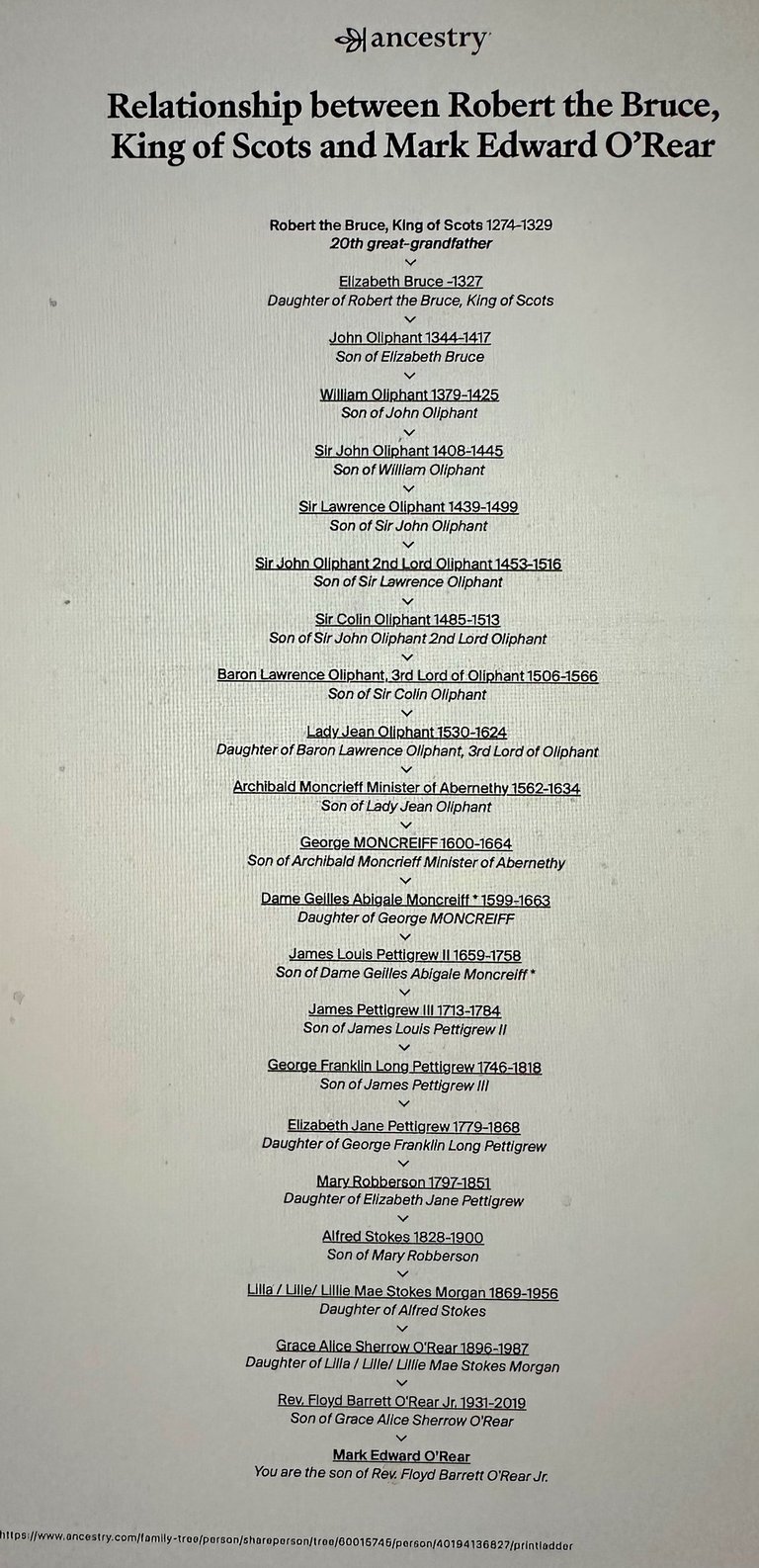

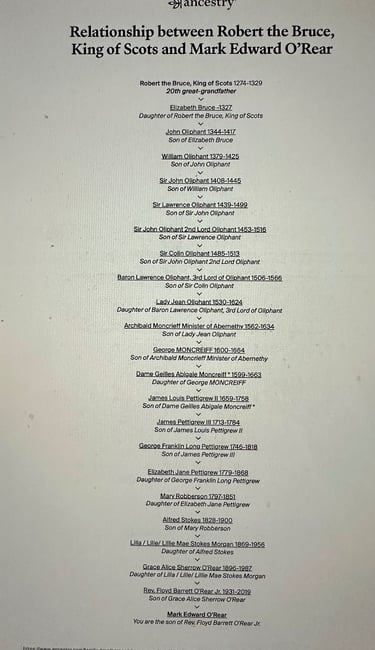

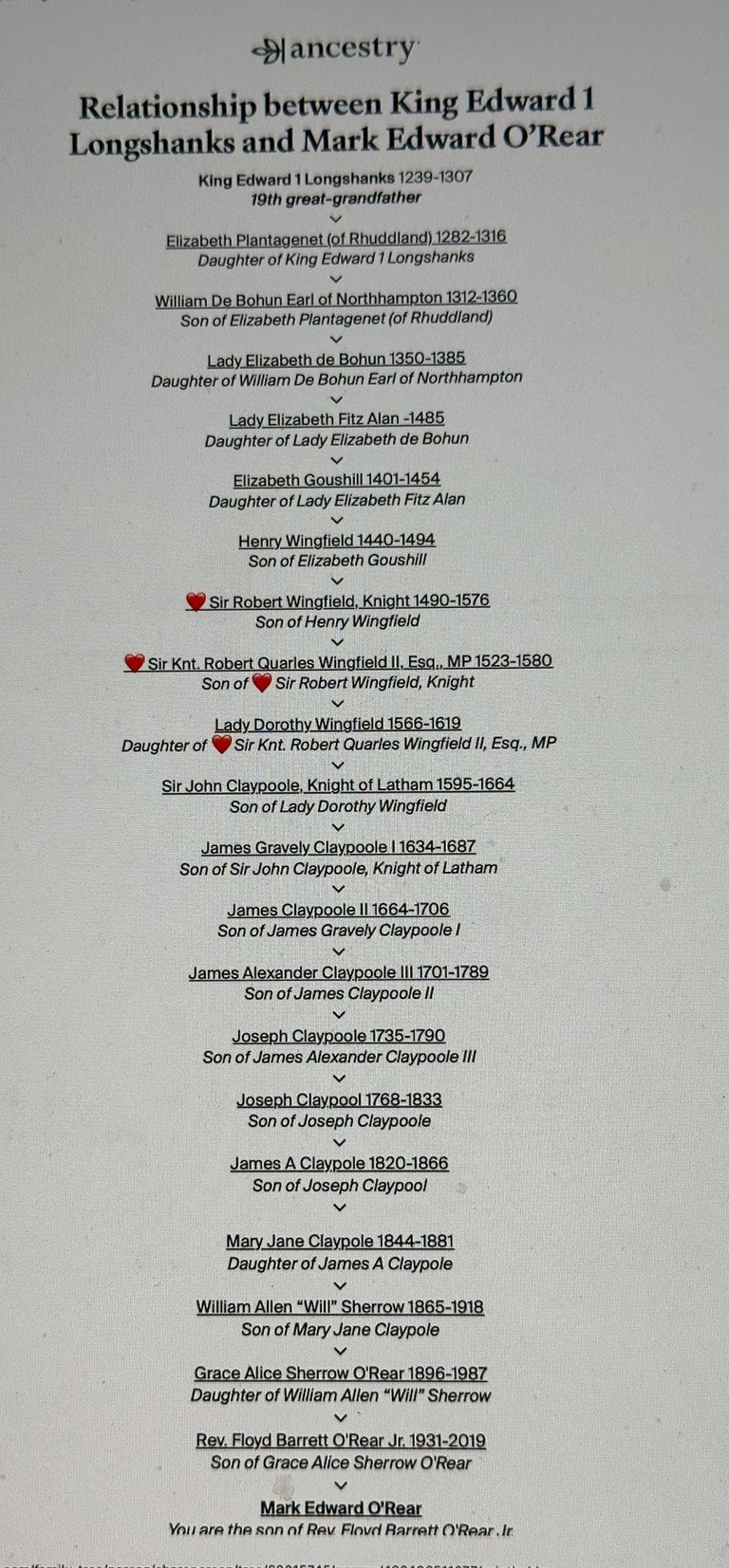

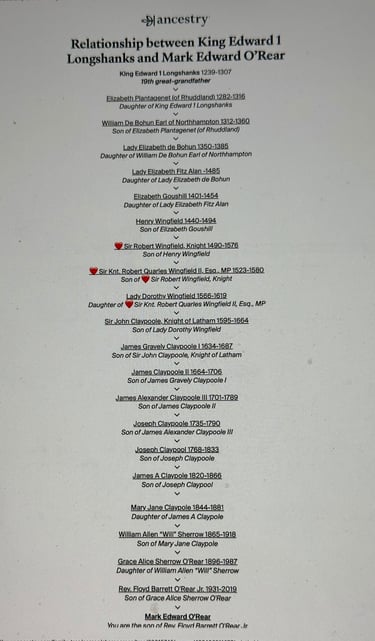

The above two lineages represent the relationship between Mark O'Rear and:

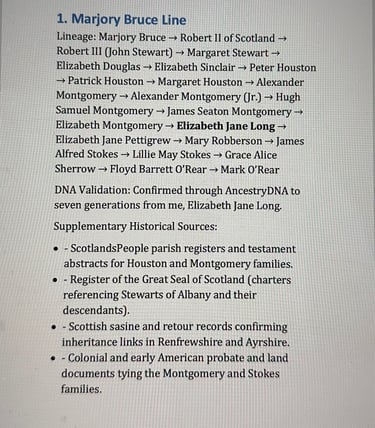

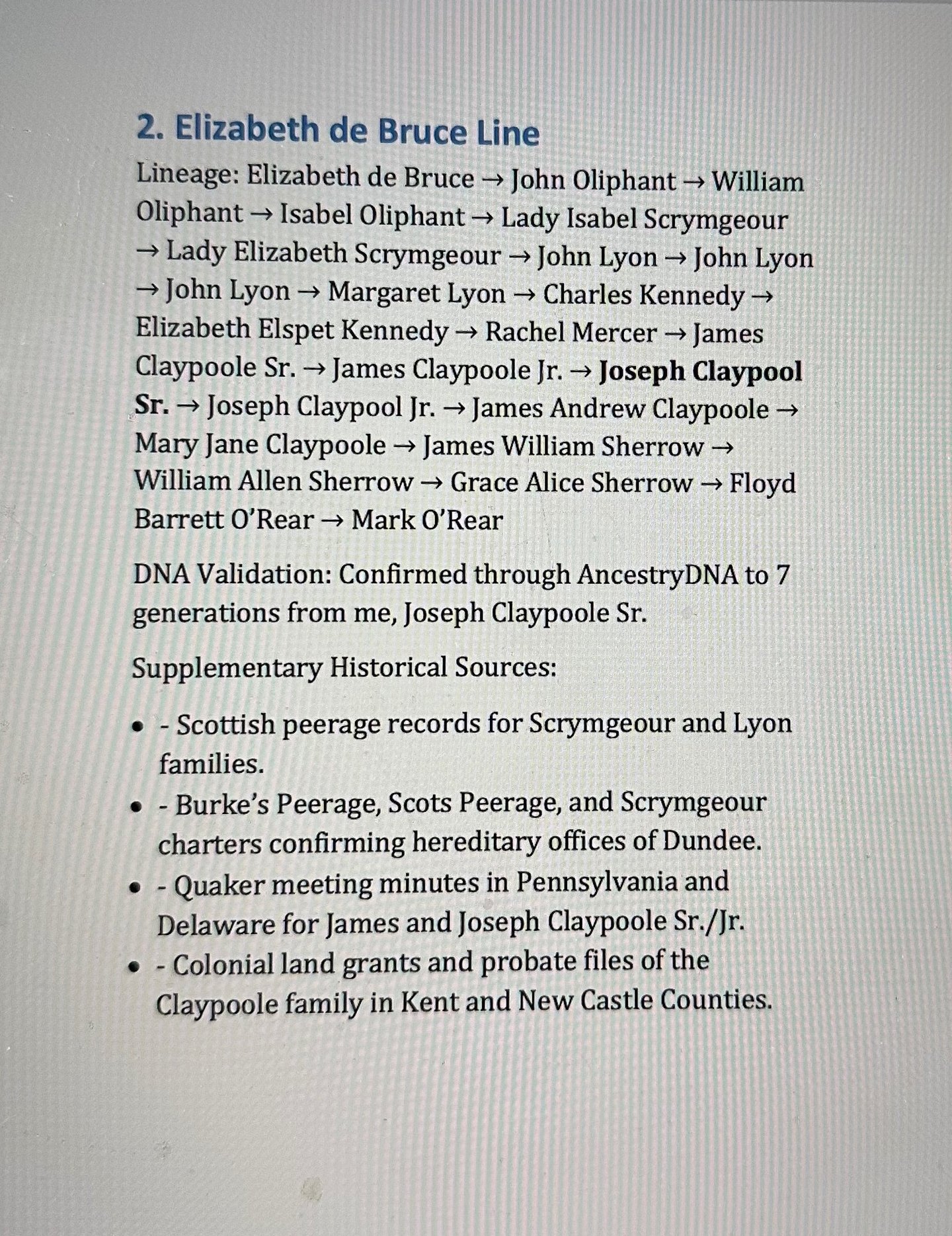

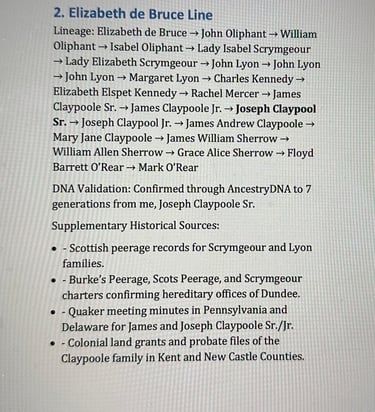

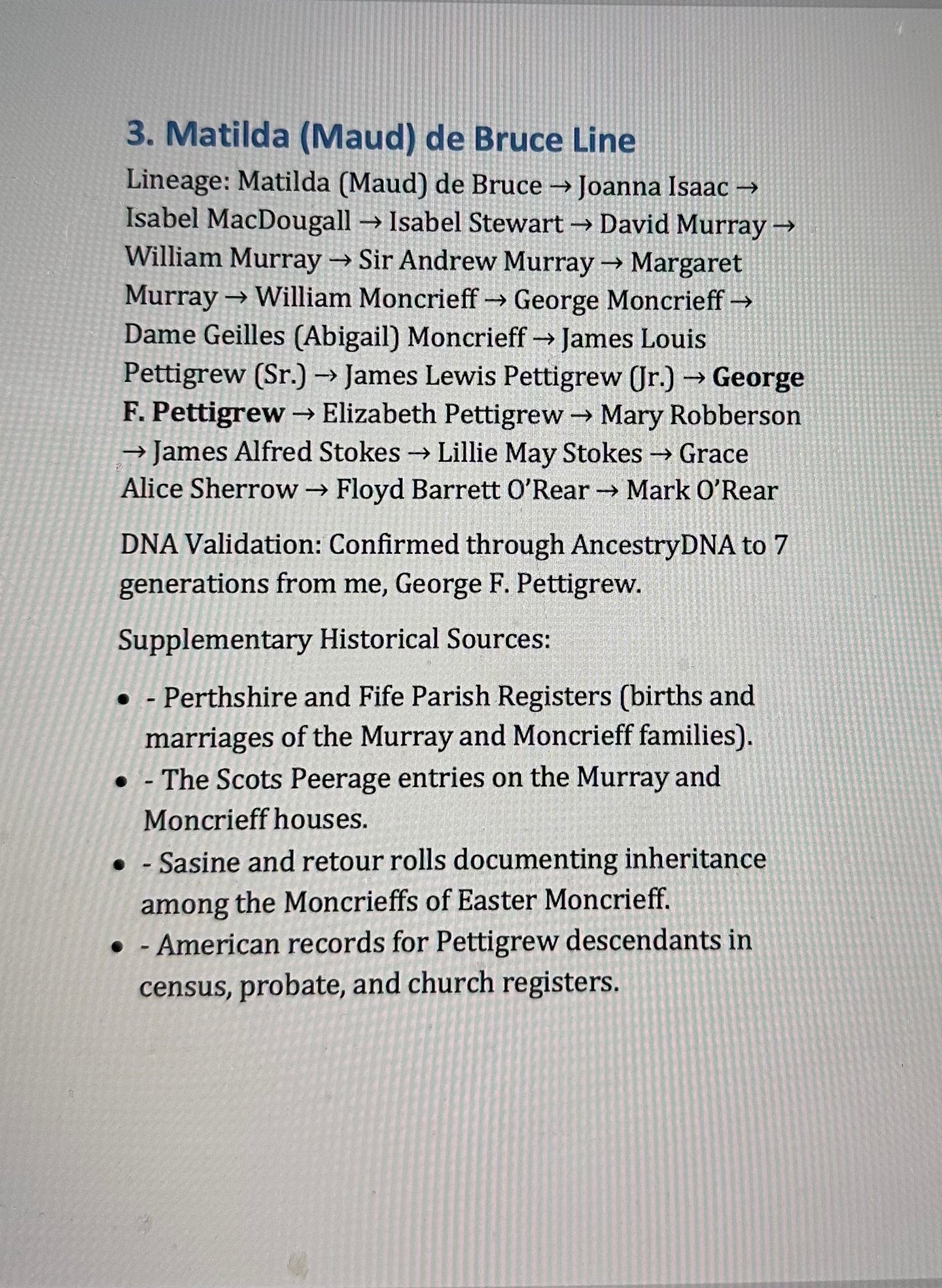

1) Robert the Bruce, King of Scots

and

2) King Edward I "Longshanks", King of England

Note: All of our O'Rear royal lineage originates with only one person, my paternal grandmother, Grace Alice Sherrow.

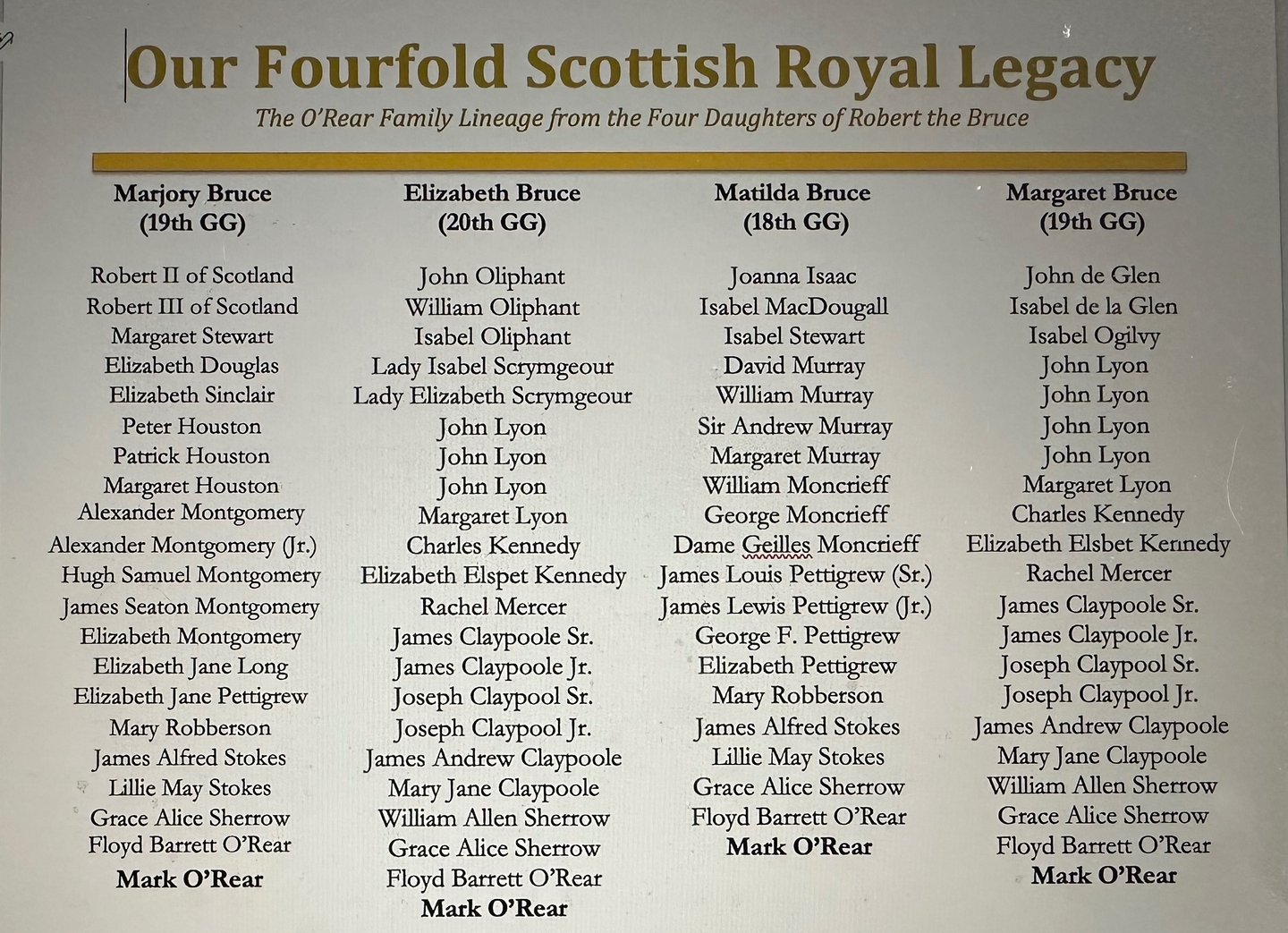

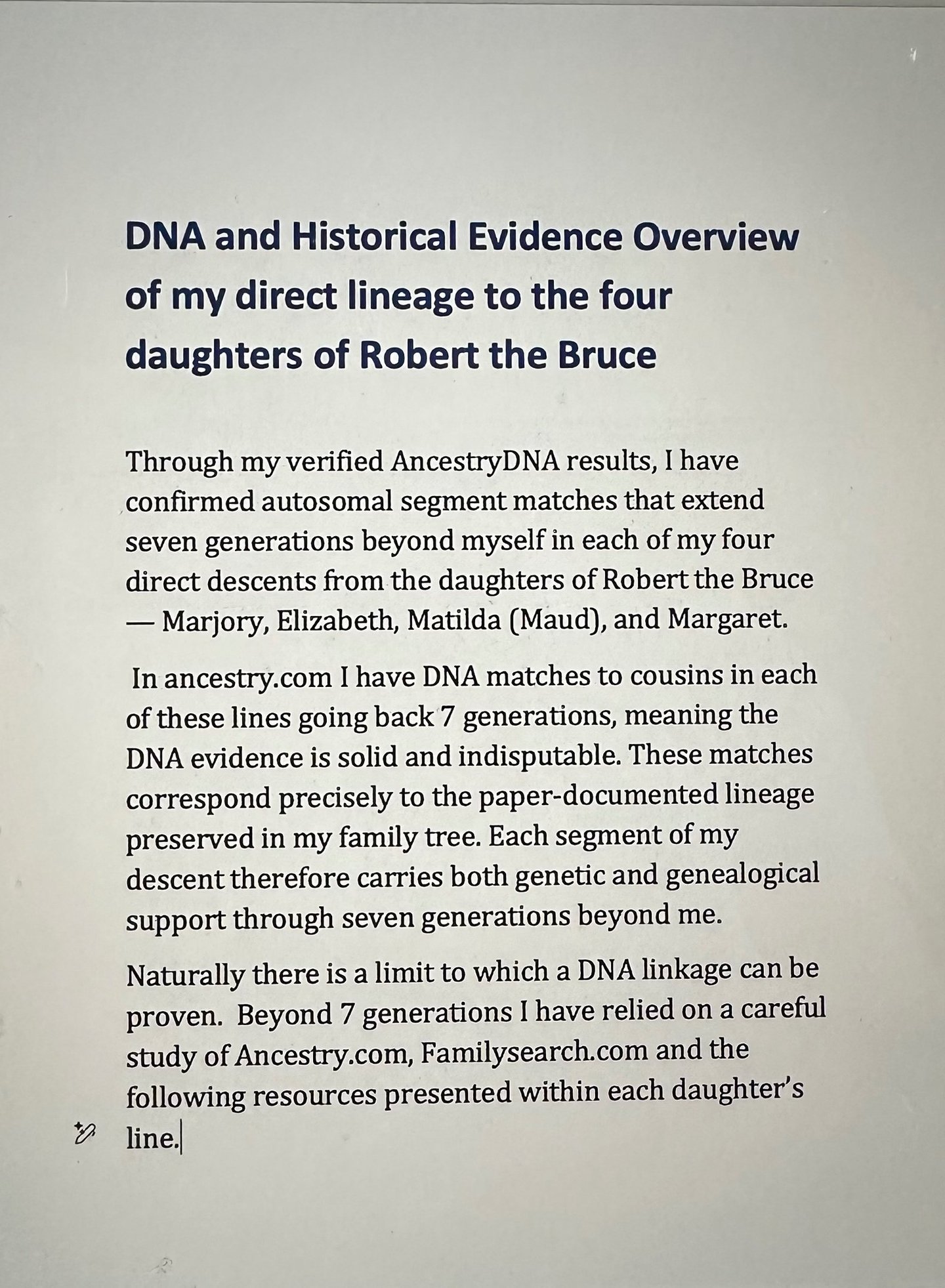

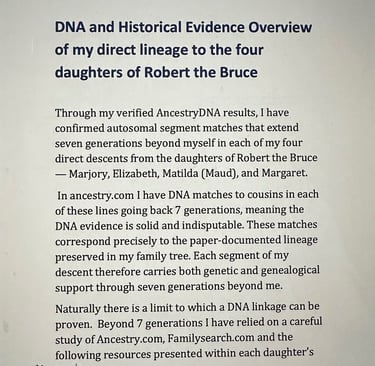

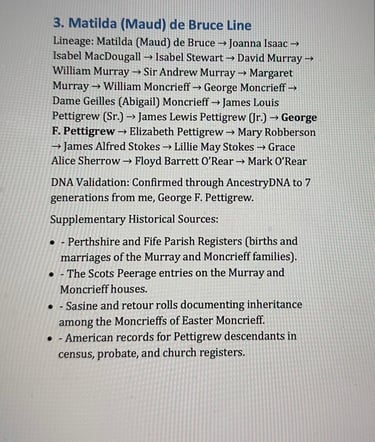

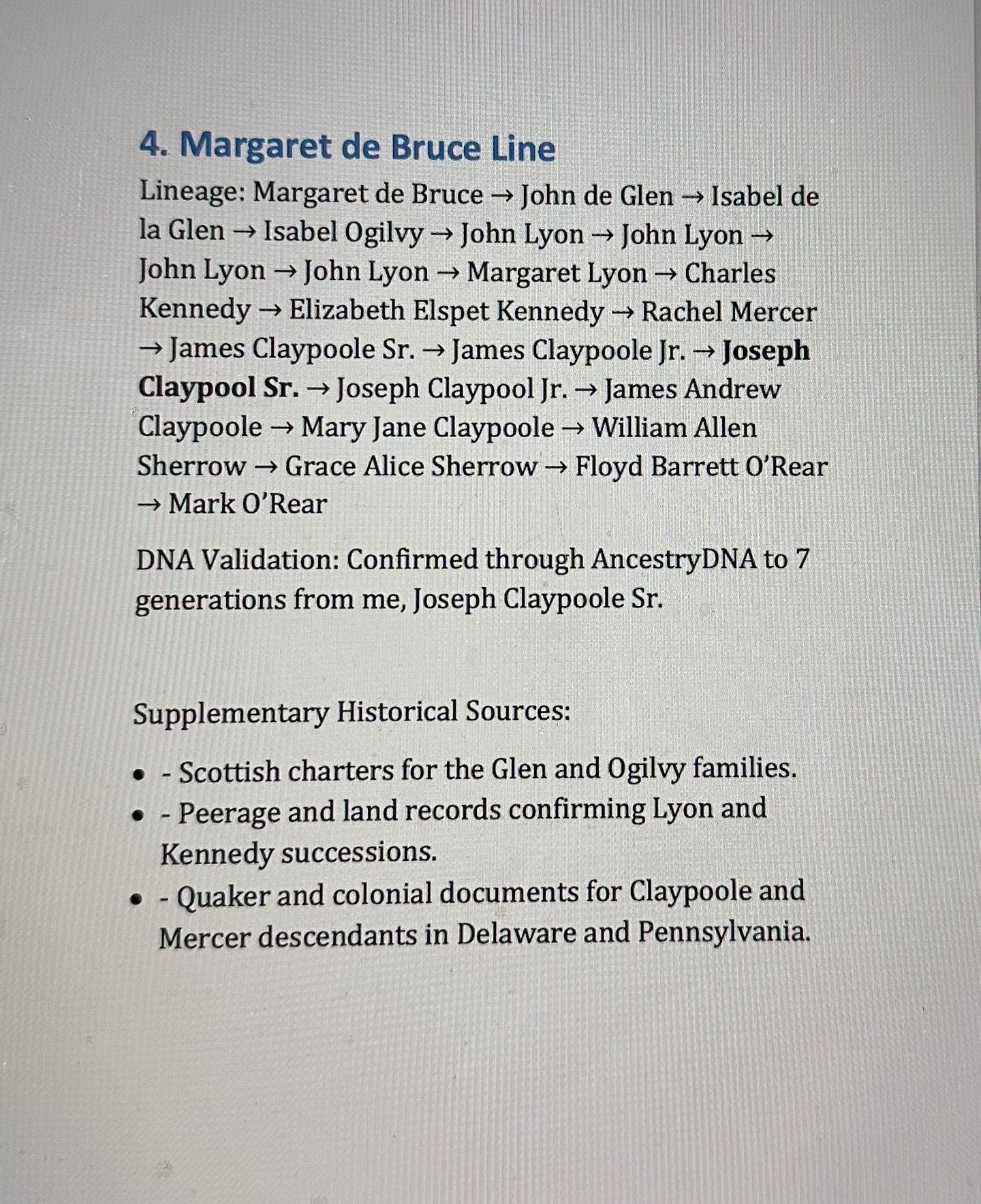

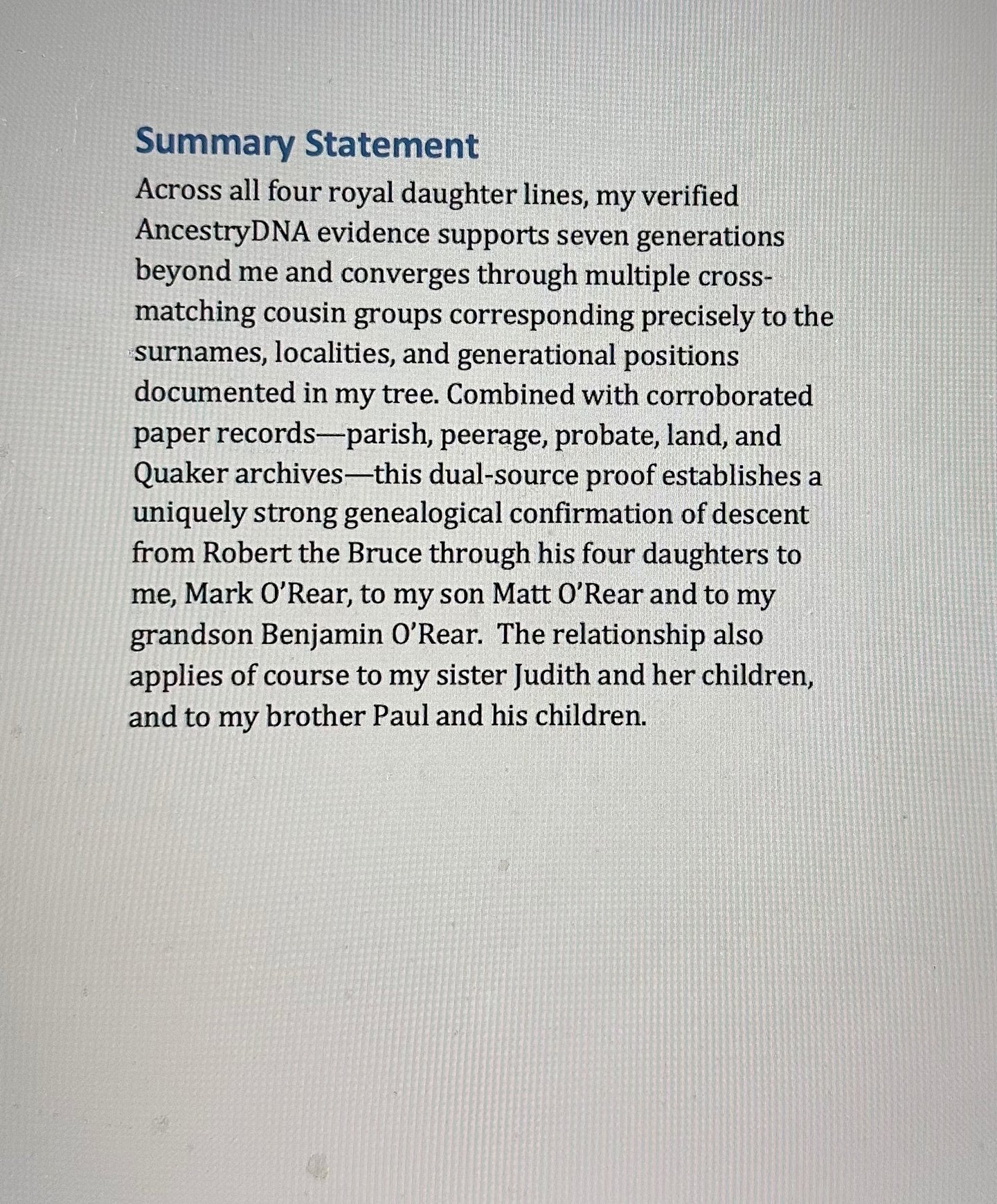

Being descended from all four of Robert the Bruce's daughters represents an extraordinary lineage, blending historical significance with the rarity of documented ancestry.

Each of Robert's daughters played a notable role in the political and social fabric of their time, and the likelihood of tracing direct descendants across all four lines is exceptionally low, especially combined with the DNA evidence that confirms these connections through seven generations.

Our remarkable heritage is not only a testament to the strength of familial ties in early Scottish history, but also to the meticulous efforts of genealogists who have compiled extensive records. Supplemented by resources such as Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.com, the rest of the lineage beyond seven generations from me (again proven by DNA) stands fortified by published genealogies and credible sources, making this ancestral journey both fascinating and rare. Certainly my family has a lot to be proud of.

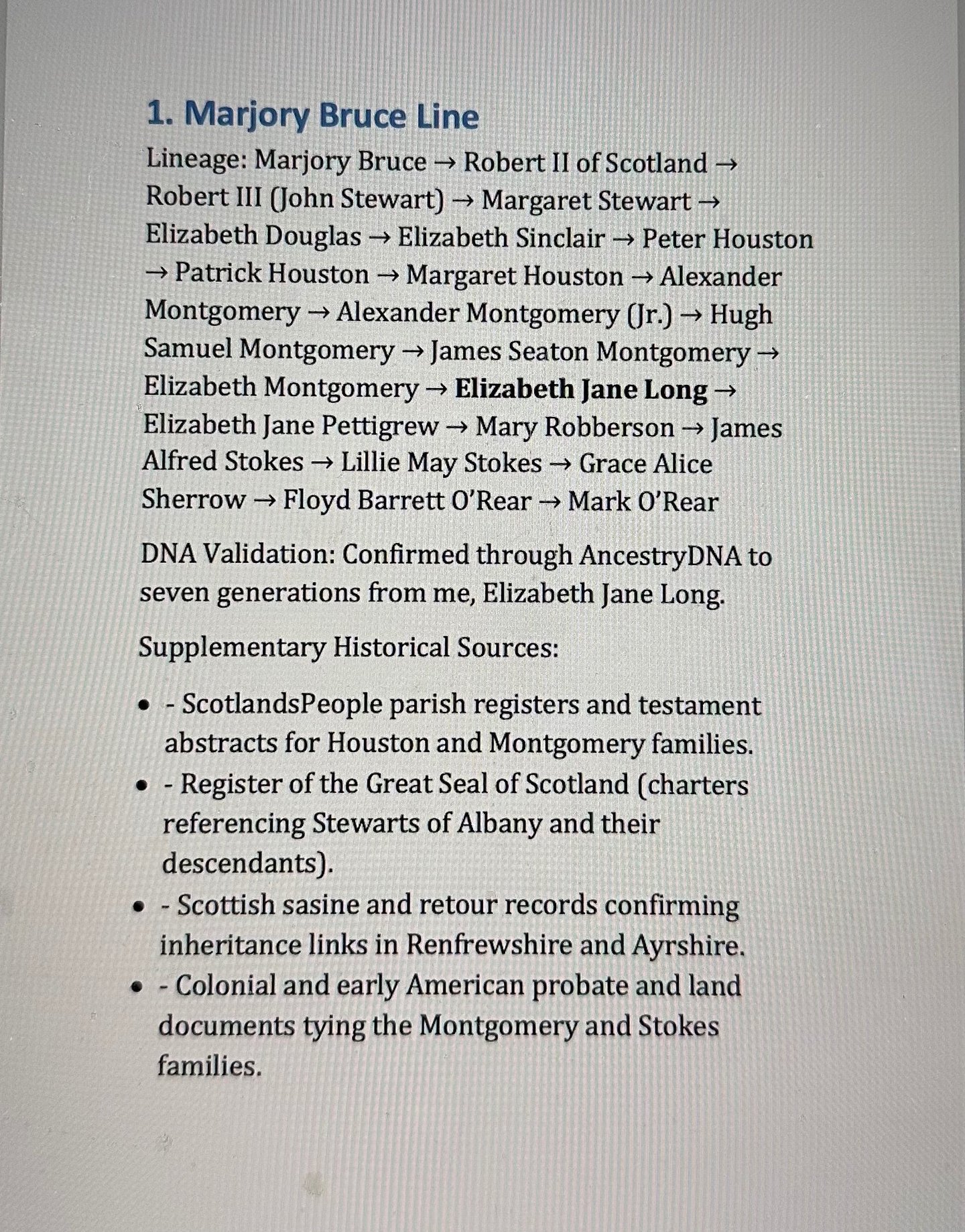

Below is a summarized chart which shows the lineage from me to Robert the Bruce's daughters.

Because of these four different paths, Robert the Bruce is either my 18th, 19th or 20th Great Grandfather!